Remembering: Terrible Jobs, Race, and Generational Changes

- mhulseth

- Aug 31, 2019

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 6, 2025

What is the worst job you ever had? What is the worst job you can imagine? What is the racial/ethnic and gender identity you associate with it? How should we think about this on Labor Day? I want to think about these things in relation to a fascinating story about my beloved Aunt Carolyn.

When the St. Paul Pioneer Press invited readers to describe “the worst jobs they ever had” for a Labor Day feature, Carolyn (then retired from college teaching) wrote about her childhood work at a small family resort with fishing cabins, near the farm in northern Wisconsin where she and my mother grew up. Her job was cleaning latrines and emptying what some might call chamberpots (for her, in the form of galvanized pails). This was in early 1950s. She was fourteen years old, too young to work at a local vegetable canning operation as my mother did. As she wrote,

The crowning task was burying fish guts from the pail under the square hole in the middle of the cleaning table. I was shown where to dig in a not very big plot of sandy earth [where the guts had been buried for years]….Each time I nudged my shovel into the ground, I found an unwavering wave of fishy rot.

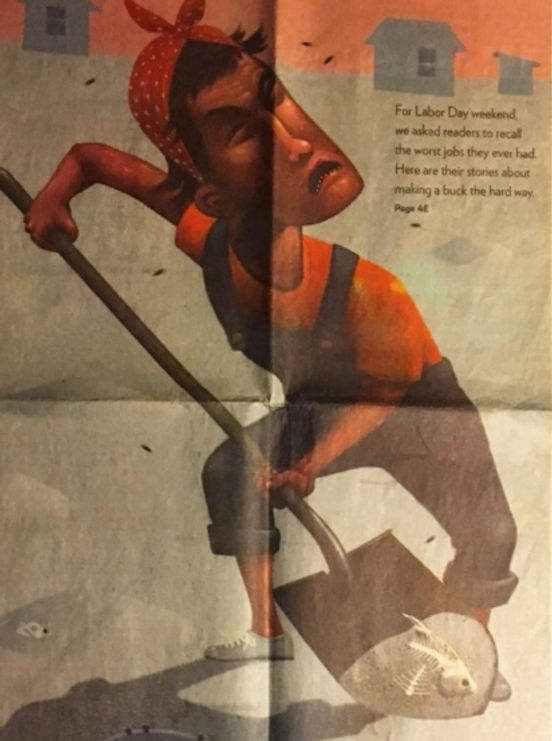

The newspaper published her story and featured it with this full-page illustration in its Sunday Life section:

My aunt’s race and to a lesser extent even gender are ambiguous in this rendering. This illustration is not even close to what she looks like—blonde and Swedish-American with a round face. Why does she look so different? Is the point that she is an everyperson—or perhaps an everywoman but, if so, far more androgynous than in real life? Could there be an implication—at least unconscious—that terrible jobs are only legible at first glance if they involve racialized Others? Or that she wouldn’t be a proper everyperson if she was too white? Or that making a white woman less white emphasizes the terribleness of the work?

I don’t ask these questions because I know all the answers. Maybe it is OK to represent terrible jobs as ambiguously racialized and gendered, given that far more raw numbers of whites than non-whites are impoverished, but meanwhile non-whites are far more likely to be impoverished. In any case I'm fascinated that they drew Carolyn this way.

It’s also worth relating Her case to my recent post about “remembering.” College kids today are further removed from the 1970s (when I started college) than I was removed from the 1930s (my mom’s childhood) when I started college. At this time, the 1930s struck me as a remote past and I was sadly ignorant about what had happened between those olden days and years when my direct experience started to pick up the slack.

The seasonal grunt work that my mom did at a canning factory as a teen, shortly after World War II—work that Latinx immigrants largely do today, and which my aunt was too young to do so she buried fish guts instead—is not far removed from the life that John Steinbeck dramatized in the Grapes of Wrath. Indeed my mom’s family was poor enough to have been characters in that book. They lost their farm to foreclosure in the 1930s, although they did not migrate. (My aunt repurchased their 1930s farmhouse, minus the cropland, much later.)

I am amazed to think that my father, born in the 1920s, farmed with horses until the 1940s, and that his family did not have indoor plumbing before my childhood in the 1960s. Meanwhile my students are amazed that I did not have a computer of any kind, much less a cell phone, until the late stages of my Ph.D work around 1990.

That’s only two generations. If we add one or two more, we are talking about things like life before electricity, even in big cities, or about impoverished Swedish peasants traveling on steamships to North America, where they made the last legs of their journey walking on trails through the woods. (This book and this one by my aunt tell some of the stories). If we then push back another one or two generations, this was mainly Ojibwe country plus a few Euro-American fur traders. The changes are mind-boggling.

I’m not trying to make one unified argument in this reflection. There is extremely much to think about if our topic opens either toward terrible jobs considered comprehensively within racialized global capitalism, or toward noticing all the important changes over the past few generations.

However, one part of my point is to notice how poverty, terrible jobs, and a lack of class privilege were and are a non-trivial issue for a great many white people. Of course It is very important not to forget white privilege—especially, in the story of my family, how how it relates to the dispossession of Ojibwe people, as well as the question of differential access to college educations and middle-class professions especially before the 1970s. Nevertheless, if such shorthand loses track of class relations, such that being “white” reduces to being affluent and exploitative, never to being aggrieved and suffering, this can badly misfire.

If an illustrated story about my aunt helps us think about US poverty having just as many white faces as black ones—fewer proportionally but more in raw numbers—or if conversely it helps us put a face that “looks like us” on hard-working immigrant families (whether in the present or the past) maybe it can do some good for a Labor Day reflection.